This page is

for high school and college students, or anyone else.

This page is

for high school and college students, or anyone else.

This website collects no information. If you e-mail me, neither your e-mail address nor any other information will ever be passed on to any third party, unless required by law. I have no sponsors and do not host paid advertisements. All external links are provided freely to sites that I believe my visitors will find helpful. This page was last modified April 1, 2010.

This page is

for high school and college students, or anyone else.

This page is

for high school and college students, or anyone else.

Everybody brings a different set of experiences to a book, a theater, or a classroom. Although I've tried to help, ultimately you'll need to decide for yourself about Shakespeare and Hamlet.

I hope you have as much fun as I have!

"Hamlet" is the first work of literature to look

squarely at the stupidity, falsity and sham of everyday life,

without laughing and without easy answers. In a world where things

are not as they seem, Hamlet's genuineness, thoughtfulness,

and sincerity make him special.

Hamlet is no saint. But

unlike most of the other characters (and most people

today), Hamlet chooses not to

compromise with evil. Dying, Hamlet reaffirms

the tragic dignity of a basically decent person in a bad world.

"Hamlet" is the first work of literature to show an

ordinary person looking

at the futility and wrongs in life,

asking the toughest questions and

coming up with honest

semi-answers like most people do today. Unlike so much of popular culture

today, "Hamlet" leaves us with the message that life is indeed

worth living, even by imperfect people in an imperfect world.

Aristotle wrote that in a tragedy, the protagonist

by definition learns something. Whatever you may think

of Aristotle's reductionist ideas about serious drama,

Shakespeare's heroes all develop philosophically.

(You may not agree with everything they decide.)

As you read the play, watch how Hamlet -- who

starts by wishing he was dead -- comes to terms with life, keeps his integrity, and

strikes back successfully at what's wrong

around him.

So far as I know, it's the first time this theme -- now so common -- appeared in world literature.

"Revenge

should know no bounds." -- Claudius

How old is Hamlet? We have contradictory information.

The gravedigger mentions that Hamlet is thirty years

old, and that the jester with whom Hamlet played as a child

has been dead for twenty-three years.

A thirty-year-old man might still be a college student.

However, Ophelia is unmarried in an era when girls usually

married in their teens, and several characters refer

to Hamlet's "youth". So we might prefer to think

that Hamlet is in his late teens or early twenties. And many people

have seen Hamlet's bitter, sullen

outlook at the beginning

of the play as typical of youth. You'll need to decide that one

for yourself.

(I think

"thirty" might be a mistake for "twenty". Richard Burbage,

who played Hamlet first, was older than twenty, and perhaps

the editor thought "twenty" must be wrong. You decide.)

Old Hamlet died during his after-lunch nap

in his garden.

The public was told that Old Hamlet died of snakebite.

The truth is that Claudius

murdered Old Hamlet by pouring poison in his ear.

Old Hamlet died fast but gruesomely.

The ghost

describes the king's seduction of the queen (the "garbage" passage)

just prior to describing the actual murder. This makes the

most sense if the queen actually committed adultery before the

murder, and that the affair was its actual motive.

Even in our "modern" age, if

a twenty-plus-year marriage ends with the sudden death of one partner,

and the survivor remarries four weeks later,

I'd believe that there had probably been an adulterous affair.

And everybody at the Danish court must have thought the same thing.

If you don't know this, you're naive.

It's not clear that Gertrude

actually knew a murder was committed, and we never get

proof that anyone else knew for certain, either.

But everybody must have been suspicious. And nobody was saying anything.

Young Hamlet is very well-liked. He is a soldier,

a scholar, and a diplomat. We learn that he's

"the glass of fashion and the mould of form", i.e.,

the young man that everybody else tried to imitate.

He's also "loved of the distracted multitude", i.e.,

the ordinary people like him, and if anything were to happen

to him, there would be riots.

Or the royal title may have gone to Claudius simply because

he married the royal widow, who he calls "our imperial

jointress".

Some people may tell you that

in the Dark Ages,

Jutland may have practiced

matrilineal descent, i.e.,

a society where family identity and inheritance is passed

through the female line. Since this is historical fiction,

and since the historical Hamlet's uncle simply held a public coup,

this seems moot.

Matrilineal descent is known among some

primitive people in our own century, and is attested to

by ancient writers on various cultures.

The advantage of this system

is that the best men tend to

get picked for hereditary positions of power.

With male-line succession, the old king is followed

by his oldest son, who may be stupid and get himself

killed quickly.

Under matrilineal descent, the old king picks the man who will

actually wield power after he is gone, but still

preserves his own genes.

In spite of what anybody else may tell you,

we know of no human culture where the men,

who are physically stronger and do the fighting, let the

women make the laws and the big decisions

(a matriarchy).

You may decide this is unfortunate.

A real anthropologist, Eric J. Smith [link is now down]

at U. Wash.,

points out that its checks-and-balances system made the Iroquois government

the "closest thing to a matriarchy ever described".

The play opens on the battlements of the castle.

It's midnight. (Shakespeare anachronistically says

"'Tis now struck twelve.")

Francisco has been keeping watch, and Bernardo comes to

relieve him.

Neither man recognizes the other in the darkness, and

each issues a tense challenge.

Francisco remarks, "It's

bitter cold... and I am sick at heart."

This sets the scene, since Shakespeare had no way of

darkening his theater or showing the weather.

The fact that each guard suspects the other of being

an intruder indicates all is not well, even though Francisco

does not say why he is "sick at heart".

Francisco leaves, and Marcellus arrives to share Bernardo's

watch. Bernardo is surprised to see also Hamlet's school

friend Horatio (who has just arrived at the castle; we never

really find out why he's here)

with Marcellus.

Marcellus and Bernardo think they have twice seen the ghost

of "Old Hamlet".

Horatio is skeptical. The ghost appears,

the men agree it looks like the old king, and Horatio

(who is a "scholar" and thus knows something

of the paranormal) tries to talk to it.

The ghost turns away

as if driven back / offended by the word "heaven" (God), and it

disappears.

The men talk about Old Hamlet.

They also talk

about the unheralded naval build-up commanded by the present king.

This is in response to an expected military invasion by the

Norwegian prince Fortinbras,

who wishes to regain the territories lost by his father's death.

The men wonder whether the ghost is returned to warn about

military disaster.

The ghost reappears. The men try to talk to it to find out

what it wants. They try to strike it. It looks like it is

about to speak, but suddenly a rooster crows (the signal

of morning) and the ghost

fades away. (As usual, Shakespeare is telescoping time.)

Marcellus relates a beautiful legend

that during the Christmas season, roosters might crow through the night,

keeping the dark powers at bay.

Claudius holds court. This is apparently

his first

public meeting since becoming king. Also present are

the queen, Hamlet, the royal counselor Polonius,

Polonius's son Laertes, and "the Council" --

evidently the warlords who support his monarchy.

Hamlet is still wearing mourning black, while everybody

else (to please Claudius) is dressed festively.

Claudius

wants to show what a good

leader he is. He begins by talking about the mix of sorrow

for his brother's death, and joy in his new marriage. He reminds

"the Council" that they have approved his marriage and accession,

and thanks them. Claudius announces that Fortinbras of Norway is

raising an army to try to take back the land his father lost

to Old Hamlet. Claudius emphasizes that Fortinbras

can't win militarily. Claudius still

wants a "diplomatic solution" and sends two

negotiators to Norway. Next, Laertes asks permission to return

to France. The king calls on Polonius.

When Polonius is talking to the king, he always uses a flowery,

more-words-than-needed style. Polonius can be played

either for humor,

or as a sinister old man. (Sinister, evil people can still do foolish

things -- like getting themselves caught spying on someone who is very upset.)

Either fits nicely with the play's

theme of phoniness.

Polonius says he is agreeable, and the king

gives permission. This was rehearsed, and Claudius

is taking advantage of the opportunity to look reasonable,

especially because he is about to deal with Hamlet, who wants to return

to college.

Claudius calls Hamlet "cousin" (i.e., close relative) and "son"

(stepson), and asks why he is still sad. Hamlet puns. His mother

makes a touching speech about how everything must die, "passing from

nature to eternity", i.e., a better afterlife. She asks him why he

is still acting ("seems") sad. Hamlet replied he's not acting, just

showing how he really feels. Claudius makes a very nice speech,

asks that Hamlet stay at the court, and reaffirms that

Hamlet is heir to his property and throne. Hamlet's mother adds

a nice comment, and Hamlet agrees to stay. He may not really have

a choice, especially since Claudius calls his answer "gentle and

unforced". Does Claudius really care about Hamlet?

Maybe. The meeting is over, and Claudius announces there

will be a party, at which he'll have the guards shoot off a cannon

every time he finishes a drink.

I.iii. Laertes says goodbye to Ophelia, his sister.

He asks her to

write daily, and urges her not to get too fond of Hamlet,

who has been showing a romantic interest in her.

At considerable length, he explains how Hamlet will not be

able to marry beneath his station, and explicitly tells her

not to have sex ("your chaste treasure open") with him.

Ophelia seems

to be the passive sort, but she has enough spunk to urge

him to live clean too, and not be a hypocrite. Laertes suddenly

realizes he has to leave quickly (uh huh). Polonius comes in

and lays some famous fatherly advice on Laertes. It's today's

self-centered worldly wisdom. "Listen closely,

and say less than you know. Think before you

act. Don't be cold, but don't be too friendly. Spend most of

your time with your genuine friends who've already done you good.

Choose your battles carefully, and fight hard.

Dress for success. Don't loan or borrow money. And most

important -- look out for Number One ('Above all --

To thine own self be true.')"

I get quite a bit of mail about Polonius's advice,

especially about "To thine own self be true." Some people see this as

Shakespeare's asking us to be totally honest in our dealings with others.

Others have seen this as a call to mystical experience,

union with the higher self.

I can't see this. The key is "to thine own self."

In Shakespeare's time, the expression "true to" meant "be loyal" or "look out first

for the interests of..."; it also meant fidelity to a romantic

relationship. This usage recurs in the Beatle' song "All My Loving".

"To be false" implies making a promise or a pretense and not

delivering. If it's clear up front that you

don't do favors without expecting something in return,

nobody can complain about being misled. The rest of Polonius's advice is otherwise totally

worldly, practical, and amoral (though not immoral) --

what one would read in a self-help book. Polonius is not

the model for scrupulous honesty. Polonius

tells Reynaldo to lie. Polonius lies to the king and queen,

claiming he knew nothing of Hamlet's romantic interest before

he saw his love letters. And Polonius tells his daughter that

everybody puts on a false front. Hearing this actually makes

the king feel ashamed.

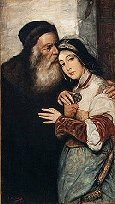

When Laertes leaves, Polonius questions Ophelia about her

relationship with Hamlet. One can play Polonius as kind

and jocular with his son, rough (even cruel

and obscene) with his daughter.

He calls her naïve, orders her not even to talk to Hamlet,

and demands to see his love letters to her.

Contemporary readers who are puzzled by this

should remember that in

Hamlet's era (and Shakespeare's), a father would

probably get less money from his future

son-in-law if his daughter was not a virgin. Polonius, of course,

pretends he cares only about Ophelia's well-being.

Hamlet, Horatio, and the guards are on the walls just

after midnight, waiting for the ghost. The king is still

partying, and trumpets and cannon go off because he's just

finished another drink. Hamlet notes that this is a custom

"more honored in the breach than [in] the observance", now a

popular phrase. (This was a Danish custom in

Shakespeare's time too. The Danish people's neighbors make fun of

them for this. Old Hamlet may not have engaged in the

practice, hence the "breach".) This fact inspires

Hamlet to make a long speech, "So, oft it chances...",

about how a person's single fault (a moral failure, or even a

physical disfigurement) governs how people think about them,

overriding everything that is good. Of course this doesn't

represent how Hamlet thinks about Claudius (who he detests

for lots of reasons), and it's hard to explain what this is doing

in the play -- apart from the fact that it's very true-to-life.

You may decide

that Hamlet is restating the play's theme

of appearance-vs.-reality.

The ghost enters. Hamlet challenges it. He asks whether it is

good or evil, his real father or a devilish deception.

He asks why it has returned, making us think

about the unthinkable and unknown ("so horridly to shake

our disposition / with thoughts beyond

the reaches of our souls").

The scene change is to indicate that the place has changed, i.e.,

Hamlet and the ghost are higher up. Hamlet demands that the

ghost talk, and he does. He claims to be Old Hamlet.

Because he died with unconfessed sins, he is

going to burn for a long time before he

finds rest. He gives gruesome hints of an

afterlife that he is not allowed to describe. (Even the

more fortunate dead returning to earth are "fat weeds".)

He then reveals

that he was murdered by Claudius, who had been having sex with

the queen. (At least the ghost says they were already

having an affair. Before he describes the murder, the ghost

says that Claudius had "won to his shameful lust"

the affections of the "seeming-virtuous queen".)

The ghost's account now becomes very picturesque.

Old Hamlet says that Claudius's "natural gifts" were far

inferior to his own, i.e., that Old Hamlet was much better

looking, smarter, nicer, and so forth. Claudius was a smooth talker ("wit")

and gave her presents.

Old Hamlet says that "lust, though to a radiant angel

linked / Will sate itself in a celestial bed / And prey on

garbage." In plain language, Gertrude was too dirty-minded

for a nice man like Old Hamlet. She jumped into bed with a dirtball.

Claudius poured poison in the king's ear.

Old Hamlet tells the grisly effects of the poison. It

coagulated his blood and caused his skin to crust, killing him

rapidly. His line "O horrible, O horrible, most horrible!" is

probably better given to Hamlet. The ghost calls on Hamlet

to avenge him by killing Claudius. He also tells him not to

kill his mother. ("Taint not thy mind..." doesn't mean to

think nice thoughts, which would be impossible, but simply

not to think of killing her.) The ghost has to leave because

morning is approaching.

When Hamlet's friends come in, he says, "There's never a [i.e., no]

villain in all Denmark..." He probably meant to say, "...as

Claudius", but realizes in midsentence

that this isn't the thing to say.

He finishes the sentence as a tautology ("Villains are knaves.")

Hamlet says he thinks the ghost is telling the truth,

says he will feign madness ("put an antic disposition on" -- he doesn't

explain why), and

(perhaps re-enacting a scene in the old play) swears them

to secrecy on his sword and in several different locations

while the ghost hollers "Swear" from below the stage.

It's obvious that Hamlet's excitement is comic, and the

scene is funny.

Hamlet calls the ghost "boy", "truepenny", and "old mole",

and says to his friends, "You hear this fellow in the cellarage."

It seems to me that Shakespeare is parodying the older play,

and even making fun of the idea of ghosts, and that he's saying,

"Don't take this plot seriously, but listen to the ideas."

Horatio comments how strange this all is, and Hamlet (who

likes puns) says that

they should welcome the ghost as a stranger in need. "There

are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt

of in your philosophy." (Ethan Hawke has "our philosophy".

I wonder if this might be what Shakespeare actually wrote.)

In Shakespeare's era, "philosophy"

means what we call "natural science". Notice that Horatio, who

is skeptical of ghosts, is the one who suggests trusting God

when the ghost appears, and who will later talk about "flights of

angels" carrying Hamlet's soul to heaven. Shakespeare's

more rational-minded contemporaries (and probably Shakespeare

himself) probably did not believe in ghosts. But

scientific

atheism

(scientific reductionism, naïve naturalism)

wasn't a clearly-articulated philosophy in

Shakespeare's era.

Some time has passed. From Ophelia's remarks in III.ii.

(which happens the day after II.i), we learn that

Old Hamlet has now been dead for four months.

Shakespeare

telescopes time. We learn (in this scene) that Ophelia has

(on Polonius's orders)

refused to accept love letters from Hamlet and told him

not to come near her. We learn in the next scene

(which follows soon after) that the king and queen have

sent to Wittenberg

for Hamlet's long-time friends, Rosencrantz and

Guildenstern (two common Danish surnames),

and that they are now here. Hamlet

has been walking around aimlessly in the palace for up to

four hours at a time.

Polonius, in private, sends his servant Reynaldo to spy on

Laertes. Polonius reminds him of how an effective spy

asks open-ended questions and tells little suggestive lies.

Polonius likes to spy.

Ophelia comes in, obviously upset. She describes Hamlet's

barging into her bedroom, with "his doublet all unbraced"

(we'd say, his shirt open in front), his dirty socks crunched

down, and pale and knock-kneed, "as if he had been loosèd

out of hell / to speak of horrors." Or, as might say, "as if

he'd seen a ghost." Hamlet grabbed her wrist, stared at her

face, sighed, let her go, and walked out the door backwards.

What's happened? Hamlet, who has set about to feign mental

illness, is actually just acting on his own very genuine feelings.

Hamlet cares very much about Ophelia. He must have hoped

for a happy life with her. Now it is painfully obvious

that

they are both prisoners of a system that will never

allow them to have the happiness that they should.

If you want to write a good essay, jot down in about 500 words

what Hamlet was thinking while he was saying nothing. Here's where

we really see him starting to be conflicted. Will he strike back,

or just play along with Claudius and perhaps marry the woman he loves

and be happy? What kind of a relationship can a man who's trying to be

upright have in a bad world? Hamlet says everything and says nothing,

just as the skull will do later.

When Hamlet acts like a flesh-and-blood

human being showing authentic emotions, people

like Polonius will say he is insane. And Polonius suggests

Hamlet is lovesick. Maybe Polonius really believes this.

Maybe he just realized that perhaps his daughter might

be the next Queen of Denmark.

The king and queen welcome Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

Claudius says that except for the death of Hamlet's father,

he's clueless as to why Hamlet is upset. (Uh huh.) He asks them

very nicely to try to figure out what's wrong so Claudius can help.

(Now Claudius might well be sincere.) Gertrude says she wants

them to make Hamlet happy, and that the good and generous king

will reward them well. Both say how much they appreciate the

opportunity, and Claudius thanks them. Often a director will

have Claudius call each by the other's name,

and Gertrude point out which is which

(lines 33-34). They go off to find Hamlet. Polonius comes in

and announces that the ambassadors from Norway have returned,

and that after their report he will tell them why Hamlet is

acting strange. Gertrude thinks that Hamlet is simply

distressed over his father's death (which Claudius thought of)

and her remarriage (which Claudius pretended he couldn't

think of.)

The ambassadors are back from Norway.

Fortinbras was indeed mounting an army to attack Claudius's

Denmark. The King of Norway was sick and supposedly

thought Fortinbras was going to invade Poland instead. (Uh huh.)

When he "learned the truth", the King of Norway arrested

Fortinbras, made him promise not to invade Denmark, and

paid him to invade Poland instead. The King of Norway

now requests that Claudius let Fortinbras pass through Denmark

for the invasion. (Denmark is on the invasion route from

Norway to Poland if the Norwegian

army is to cross the sea to Denmark.

And we know a sea-invasion was expected from the

amount of shipbuilding mentioned in I.i.)

This all seems fake and for show, and

probably Claudius (who doesn't seem at all surprised)

and the King of Norway had an understanding

beforehand.

At this time, Hamlet (who may have been eavesdropping), walks in

reading a book. Polonius questions him, and Hamlet pretends to

be very crazy by giving silly answers. They are pointed,

referring to the dishonesty of Polonius ("To be honest,

as this world goes, is to be one man picked out of ten thousand.")

Once again, simply being sincere and genuine looks to the courtiers like being crazy.

Hamlet is well-aware

that Polonius has forbidden Ophelia to see him, and he refers

obliquely to this. Polonius notes in an aside (a movie director

would use a voice-over), "Though this be madness, yet there is

method in it" -- another famous line often misquoted. The speech

of the insane, as Polonius notes, often makes the best sense.

Why is Hamlet pretending to be comically-crazy?

He said he would "put an antic disposition on" just after he saw

the ghost. You'll have to think hard about this, or suspend your

judgement. Shakespeare was constrained by the original Hamlet story

to have Hamlet pretend to be comically insane, and for the king to try

to find whether he was really crazy or just faking. But Hamlet is also

distraught, and the play is largely a study of his emotional turmoil

while he is forced to endure a rotten environment.

You might decide that Hamlet, knowing that his behavior is going to be

abnormal because he is under stress, wants to mislead the court into thinking

he is simply nuts rather than bent on revenge. (Of course, this is completely

unlike his motivation in the original story, where he pretends to be insane

so that people will believe he poses no threat.) I've never been able to

decide for myself.

Polonius leaves, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (who have been watching)

enter. Hamlet realizes right away that they have been sent for.

They share a dirty joke about "Lady Luck's private parts" that would

have been very funny to Shakespeare's contemporaries, and Hamlet calls

Denmark a prison. When they disagree ("Humor a madman"), Hamlet says

"There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so. To me

it is a prison." Hamlet is making fun of how naive his fake friends are,

and perhaps wishing he knew less than he did.

(Note that Hamlet is obviously not

referring to the idea that there are no moral standards common

to the whole human race --

as do certain contemporary "multiculturalists". The theme

of right and wrong pervades the play.)

The idea that attitude is everything was already

familiar from Montaigne, and from common sense.

Again we have the theme of the play -- Hamlet chooses NOT to

ignore the evil around him, though everybody else has, or pretends to have,

a "good attitude" toward a terrible situation

The spies suggest Hamlet is simply too ambitious.

This is ironic, since they are the ones who are spying on their friend

for a king's money. Hamlet replies, "O God, I could be bounded

in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not

that I have bad dreams." The friends continue to play on the

idea that Hamlet's ambitious are being thwarted, sharing some

contemporary platitudes about the vanity of earthly ambitions.

But it seems (from

what will follow) that Hamlet's remembering the time when the world

seemed like a much happier place -- before he saw the wrongs as

they are. Hamlet then questions the men

again about the purpose of their visit. If they actually cared,

they would say, "Your family asked us to come. We are all very

worried about you." Instead, they pretend they just dropped by to visit,

which is stupid. Only when Hamlet asks them "by the rites of our

fellowship" (i.e., by our secret fraternity ritual) do they have

to tell the truth. (In my own

college fraternity, we have the same understanding and a

nearly-identical formula.)

The two friends then tell Hamlet that some traveling entertainers

will be arriving that evening. They used to have their own theater,

but some child-actors became more popular (a contemporary allusion

by Shakespeare to the late summer of 1600),

and the adult actors took to the road. Hamlet

compares the public's changing tastes to the way people feel about his

uncle. (Q2 omits the reference to the child actors, but

without it, the transition between the actor's losing popularity

and the new king gaining popularity makes no sense, so it

cannot be an interpolation.) Hamlet quickly and obliquely tell his

friends he is only faking ("I am but mad north-north-west. When

the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.")

Hamlet asks Polonius to treat the actors well. Polonius says he'll

treat them as they deserve -- actors were considered undesirables.

Hamlet says, "[Treat them] better. Use every man after his

desert [i.e., deserving], and who shall [e]scape whipping?" Hamlet

gets an idea. He

asks for a performance of "The Murder of Gonzago", with a short

speech by Hamlet himself added. (Don't try to

figure out what happened to this speech.)

Everybody leaves.

Some commentators

have taken Hamlet at his word, and thought he is obsessing

and/or depressed, both of which interfere with action.

But it seems to me

that this is simply a human response to being unable to do anything --

we blame ourselves instead of circumstances. Especially, Hamlet

is upset that he needs to make compromises with the world in which

he finds himself. Perhaps this is confusing -- since Hamlet

still doesn't know for sure that the king is guilty. But it's

true to the human experience, and the ideas that Shakespeare

has been developing. I hope you'll think about this, and decide

for yourself.

The next day, the

two spies visit with the king and queen, as well as Polonius,

who has brought Ophelia. They say what

everybody knows -- Hamlet's crazy talk

is "crafty madness" to hide a secret,

and that he really is upset about something. They invite the

royal couple to the play, and the king seems genuinely glad that

Hamlet's found something he will enjoy.

The king sends the queen and the spies away.

Polonius gives his daughter a book, plants her where

Hamlet will find her, and tells her to pretend

she is reading. Polonius tells her (or to the king?),

"It's all right, dear,

everybody pretends." ("With devotion's visage / and pious action

we do sugar o'er / the devil himself.") The king sees the

application to himself, and says,

"No kidding." ("How smart a lash that speech doth

give my conscience!") This is powerful -- we suddenly learn

that the king feels horrible about his own crime. Maybe this

surprises us.

If Polonius is a sinister old man

and knows all about the murder, the king

says this directly to him as they are out of earshot of Ophelia.

Polonius can grunt cynically in response --

there's nothing really to say in reply.

If Polonius is a foolish old man,

the king says this as an aside. We have just learned that the

king really does hate his crime, and suffers under a "heavy

burden".

III.ii.

Hamlet gives an acting lesson, mostly about being genuine.

He wants to show people -- body and mind --

as they are. So does Shakespeare.

He talks with Horatio, and we learn that Horatio is a poor

boy who's had bad luck

but who doesn't complain. He and Hamlet are genuine friends

who know they can trust each other. (A stoical, kindly friend

like Horatio is a good choice for the Hamlet who we first meet.

After all, he's considering suicide -- a posture that he will

outgrow as the play goes on.)

Hamlet says, "Give me that man / That is not passion's slave,

and I will wear him / In my heart's core, ay, in my

heart of heart, / As I do thee." Our society doesn't talk

as much about male bonding as Shakespeare's did. Around

1600, guys --

including Shakespeare -- commonly

wrote poems for each other, and nobody thought this was weird.

It seems to me that the entire

Danish court

realizes (or will soon realize)

that Old Hamlet was murdered by Claudius, and that

Hamlet knows too. (Hamlet is about to break through

his own mother's denial.) Hamlet and Horatio congratulate

each other. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern come back in looking

for Hamlet, telling him the king is very angry (duh) and

that his mother wants to see him (king's orders). Hamlet

gives them goofy answers, intending to insult them

rather than deceive them. Guildenstern asks for straight

answers. Rosencrantz says, "My lord, you once did love me",

and asks why Hamlet is upset. Hamlet's response is to

tell his friends to play the recorders that the actors

brought. Neither knows how. Hamlet says they should be able

to, since "it is as easy as lying". When they still refuse,

Hamlet tells them that they can't play him like they would

an instrument.

Once again, Hamlet's genuineness looks like madness.

Polonius comes in, and Hamlet, still talking

crazy, gets Polonius to agree that a particular cloud looks like

each of three different animals. (Appearance

versus reality.) In an aside, he says to

the audience that this is as good a job of acting crazy as he can manage.

Alone on stage, Hamlet says, "Now could I drink hot blood /

And do such bitter business as the day / Would quake

to

look on." (Unfortunately for everyone, he is about to

do just that, by stabbing Polonius.)

He says that he'll keep his temper and not hurt

his mother physically.

III.iii.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are back with the king, who

says Hamlet is dangerous and that he will send

him with them to England with a "commission".

The two spies talk in Elizabethan platitudes about

the sacredness of kingship, the importance of

stability in a monarchy, being "holy and religious",

and so forth. (Uh huh, uh huh.)

The spies leave. Polonius enters and

tells Claudius he is going to hide in the bedroom.

Claudius thanks him.

Hamlet enters, sees the king

unguarded. Perhaps following the plot

of the old play, Hamlet spares

him, since if he's killed during

prayer his soul might end up going

to heaven. The actor can say, "And so he goes to h.... [long pause, he

meant to say "hell"], uh, heaven".

Somebody will ask you to say that Hamlet is a very bad person for

wanting to wait for his revenge until the king is more likely to

end up going to hell. It seems to me that this scene

probably was known from the older "Hamlet" play. Whatever you make of it,

the King's speech is among my favorites.

Shakespeare has

added a special irony that's apparent in Claudius's words

-- he was not even able to pray, only struggling.

Polonius hides behind a curtain ("arras")

in the bedroom. Hamlet comes in. The queen

yells at him. He yells back.

Hamlet accuses her of killing his father (i.e., complicity, perhaps just

not thinking about what she should realize her first husband was murdered).

Of course, there is no

evidence she actually knows. (In the quarto version, she says she has no

knowledge of the murder.) Gertrude seems puzzled. Notice that Hamlet doesn't

even mention that he is watching his mother in the "Mousetrap" scene; of course,

she would pass the test.

Gertrude gets frightened and yells

"Help!" Polonius behind the curtain yells "Help!" In the

stress of the moment, Hamlet stabs him to death through the curtain.

(As a pathologist who's seen plenty of real-life murder, this fits

perfectly with the most common scenario. Someone who is already

very upset feels their basic dignity and personal space has been violated.

And Polonius has done this to Hamlet.)

Trying to avenge a murder and set things to right,

Hamlet has just committed another murder -- this

one senseless. But

Hamlet is so focused on his mother that he does not even

pause to see who he has killed before he accuses his mother

of complicity in the murder

of his father. (Hamlet doesn't know for sure.)

When Polonius's body falls out from behind the curtain,

Hamlet remarks he thought it was the king

(who he was just with, someplace else), and talks about

how being a busybody is dangerous. He turns immediately

back to his mother, who is baffled and evidently

is just now realizing herself

that Claudius is a murderer. (In the quarto version,

the queen says something to the effect that she has just

now learned of Claudius's guilt. Perhaps some

of the original text of the play has been lost from the folio version.)

Hamlet's

speech to his mother has less to do with the murder

and how it is wrong than with her sexual misbehavior and

her not mourning her loving first husband.

Many of us today will see this as a sexual

double-standard from Shakespeare's own time. Maybe this is true;

in any case, I'm old enough to remember the double standard and how wrong it was.

Instead, focus on the queen's

adultery and ingratitude, wrongs against her former husband.

Now that Hamlet has killed Polonius, he has become himself a murderer

and the object of Laertes's just quest for revenge. No reasonable

person would consider Hamlet either as culpable as Claudius,

or excuse him entirely. (A jury today might be understanding,

and even a prosecutor might say, "Justifiable homicide.")

Just recently, we heard Hamlet talk

about his own "patient merit". Now Hamlet is all-too-human.

But there's something else. In this scene, Hamlet and his mother reaffirm

their love for one another. From now on, Hamlet will no longer talk

about life not being worth living. Perhaps this is the real turning-point

of the play.

The queen tells the king what has happened to Polonius, and that

Hamlet is insane. The king says he will need to send Hamlet

off immediately, make some kind of excuse for him, and think

how to protect the king's own good name (uh huh). Line

40 is defective. It should conclude with something about "slander".

IV.ii.

Hamlet has hidden Polonius's body, and when the spies

question him, he talks crazy-crafty but says clearly that he

knows they are working for the king and against him.

He warns them

that this is dangerous. By now the two spies do not

even pretend they care about Hamlet.

IV.iii.

IV.iv.

Fortinbras's army crosses the stage, and Fortinbras drops a captain

off to visit the Danish court. The captain meets Hamlet, Rosencrantz,

and Guildenstern. Hamlet asks about the army, and the captain

says that Norway and Poland are

fighting a stupid war over a worthless piece of land.

Two thousand people are going to get killed over this nonsense.

Hamlet says this is the result of rich people

not having enough to do, a hidden evil

like a deep abscess rupturing into the blood.

Alone on stage, Hamlet contrasts himself to Fortinbras.

Hamlet has something worth doing that he hasn't yet done.

Fortinbras is busy doing something that isn't worthwhile.

Hamlet reaffirms his bloody intentions. You may be asked to

comment on this passage. You'll need to decide for yourself

exactly what it means. If you've made it this far, you're up to the

challenge.

A courtier tells the queen and Horatio that Ophelia is semi-coherent,

talking about her dead father and that the world is full of deceptions

("There's tricks in the world!") The queen does not want to

talk to her; in an aside, she says it will trouble and expose her

own guilty conscience.

Since the scene in her bedroom, the queen has felt guilty.

She speaks of her own "sick soul" and of "sin's true nature";

she also worries if she can keep her own composure with her own

bad conscinece ("So full of artless jealousy is guilt, it spills itself in fearing

to be spilt.")

Horatio suggests that the queen should

see Ophelia just for

political reasons. Ophelia comes in, singing a song about

a dead man, then one about premarital sex. When she leaves,

the king talks to the queen about all the wrong things that have

happened -- Polonius killed and quietly

buried without a state funeral,

Hamlet sent ("just[ly]") away, the people confused

and upset, and Laertes on his way back, angry. (The king

is, as usual, a hypocrite; everybody knows how

the trouble really started.)

IV.vi.

Horatio gets a letter from Hamlet.

Supposedly he boarded a pirate

ship during a sea scuffle. The pirates

are bringing him back

home, knowing they'll get some kind of favor

in the future.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are on their

way to England and Hamlet will have more to say about them.

IV.vii.

Before you

decide that you cannot suspend your disbelief, think about what's

really going on.

The king knows that the court knows that he's

already a murderer, and that they don't care. So nobody

will do anything even when the king and Laertes kill Hamlet

treacherously in plain view.

Two men are digging Ophelia's grave. One asks whether someone

who tries to go to heaven by the short route (suicide)

can be given Christian burial. In Shakespeare's time

(as Hamlet already mentioned in I.ii.), suicide was considered a

sin, and sometimes even unforgivable. Suicides would ordinarily

be buried in unconsecrated ground without a Christian service.

Sometimes they'd be buried at a crossroads (as a warning to everybody

not to do the same), and sometimes with a stake through the

heart (to prevent them from rising as undead, of course.)

The men joke about how politics has influenced the coroner's

decision to allow Christian burial. They parody lawyer talk

("Maybe the water jumped on her, instead of her jumping into

the water. Or maybe she drowned herself

in her own defense.")

They say what a shame it is that, in our corrupt world, rich people

have more of a right to commit suicide than do poor people.

In the medieval and renaissance world, it was the special privilege

of the court jester to tell the truth. He could do

this without fear of reprisals.

In Shakespeare's

plays (notably "Twelfth Night", "As You Like It", and "King Lear"),

the jester's role as truth-teller is central. "Hamlet" has dealt with

the themes of honesty, dishonesty, and truth-telling.

In this most famous scene of all,

Yorick tells the truth without saying a word.

We all end up in the same

place, dead.

V.ii.

Hamlet is explaining to Horatio about how he substituted

his own letter to the King of England, ordering the execution

of the spies. (He used flowerly language, though he hated doing it --

he even mentions that he was trained to write like that,

and worked hard to forget how. Again, this is the theme

of sincerity.)

Hamlet already had a pretty good idea of what

the English trip was all about, so his having a copy of the royal

seal, and some wax and paper, is no surprise (as he already indicated

at the end of the bedroom scene.) Surprisingly, Hamlet talks about

reading and changing the letters on an impulse, and has a

famous line, "There's a divinity that shapes our ends / Rough-hew

them how we will." Rough-hew was to carve the basics of a

woodcarving or sculpture, with the fine-shaping to follow.

Horatio (who seems more inclined to

faith in God than do the other characters) agrees: "That is

most certain." Since this doesn't make perfect sense

with the plot, Shakespeare probably placed it here for

philosophic reasons, especially given what is about to happen --

coincidences ("Providence"?)

are going to work events out for Hamlet's cause.

There

seems to be some mysterious design behind life that makes things

work out and gives life its meaning. Unfortunately for Hamlet

and other decent people, it doesn't always bring about altogether

happy endings. Still, it's grand being part of

things. One can find similar ideas in Montaigne,

Proverbs 16:9, and the modern Christian saying, "A

person proposes, God disposes."

Bring your own life experience -- do you know of anyone who had been considering suicide

who was comforted and perhaps dissuaded by the notion that somehow

the universe (if not a personal God) would "somehow work everything out"?

Do you think this is true? I can't answer.

Osric brings Laertes's challenge, Hamlet accepts.

The king has bet heavily on Hamlet, probably to divert suspicion.

Don't try

to figure out the terms of the bet -- the two accounts

contradict each other. Hamlet admits

foreboding to Horatio, and both suspect foul play

is imminent. But Hamlet

decides to go forward anyway. "We defy augury" -- Hamlet is not

going to let his apprehensions interfere with his showing

courage and doing what he must. "There is special providence in

the fall of a sparrow." This is an allusion to the gospel. God

knows every sparrow that falls. Mark Twain ("The Mysterious Stranger")

pointed out that the sparrow still falls. Hamlet is about to die,

too, although God is watching. Hamlet notes that death is going

to come, sooner or later. "The readiness is all" -- being ready to

live and die with courage and integrity

is all the answer that Hamlet will

find for death. Hamlet points out that nobody really knows

what death is, so why be afraid to die young? "Let be" -- don't

fight it. Is "Let be" the answer to "To be or not to be?" (!).

As the king expected, Hamlet is not at all

suspicious about the swords, and merely asks whether they're

all the same length. In the first round, Hamlet

tags Laertes (who is

thinking about the poison and perhaps doesn't have

his heart really in it). The king drops the poison in the

cup, pretending he thinks it's a pearl. (Okay, this is silly.)

Whether the court thinks the pearl is to be dissolved in acidified

wine and drunk (occasionally done as conspicuous-consumption),

or is a gift to Hamlet, you'll need to decide for yourself.

The king probably takes a drink (from another cup, or

he drinks before the poison is dissolved,

or he just pretends to drink.)

The queen mentions that Hamlet is "fat and out of breath". Fat

just means "sweating", so she wipes his forehead.

In the second round, Hamlet hits Laertes again. The queen

grabs the cup and drinks despite the king's warning.

We'll never know whether she has just realized what is

going on, and wants to save Hamlet's life and maybe

end her own miserable existence. (She does realize

quickly that the cup is poisoned. People who are really

poisoned without their knowledge just think they are suddenly

sick.)

In the final scene, Fortinbras happens

by, as do the English with word of the spies' execution.

In the last irony, Fortinbras has gotten his land back,

and his own father's death avenged. Horatio says he'll

tell about "accidental judgments", i.e., people have gotten

their just deserts through seeming accidents -- the theme of

God working in the world to make things right.

Fortinbras calls for military honors to be shown Hamlet's

body. Some people will see this recovery of ceremonial

to mean things are right with the world again. Others

will simply see one more example of power passing in an

unfair world -- as it was in the real Dark Ages.

In Ingmar Bergman's production of "Hamlet", Fortinbras's

words, "Bid the soldiers shoot!" is their signal to

pull out their guns and slaughter Horatio and the rest of the

surviving Danish court.

The Historical Hamlet

was the son of a

Danish "King of the Jutes",

who lived during the Dark Ages.

Michael Skovmand, Dept. of

English at U. of Aarhus, Denmark,

shared this with me:

In Saxo, Hamlet pretends to think that the beach sand is ground grain.

This is ancient, being repeated explicitly in an old Norse saga (the Prose

Edda) that refers

to the ocean-wave nymphs "who ground Hamlet's grain". (Kennings

sometimes alluded to other stories that the audience would know.)

The ancient Roman, Lucius Junius Brutus, also feigned insanity

while awaiting his revenge. This gave the family its name ("brute" =

unthinking animal), and it was passed along to the Brutus who

killed Caesar. David (I Samuel) also once feigned madness to

deceive Saul. In our era, organized crime leader

Vincente Gigante is said to have feigned

madness.

There is a historical novel, now hard to find, about the historical Hamlet

entitled "The War of Jutish Succession".

Saxo Grammaticus "Historia Danica", written

around 1200, presents a highly-fictionalized

(actually silly) version of the story.

Belleforest's "Histories Tragiques"

was a book of stories in French from 1576. Belleforest

adapted Saxo's historical fiction.

There was an English

translation in 1608, "The History of Hamblet" (sic.); it borrows

Shakespeare's "A rat! A rat!", and specifically makes the

"covering" through which the spy is stabbed into a wall hanging.

My link to Belleforest in translation is now down. Please let me know if

this ever reappears online.

Once you get past the

minor difficulties posed by the language,

you'll probably enjoy "Hamlet" -- and not just

for its action.

Once you get past the

minor difficulties posed by the language,

you'll probably enjoy "Hamlet" -- and not just

for its action.

Shakespeare's "Hamlet" is full of talk about death,

dead bodies, murder, suicide, disease, graves, and

so forth. And there is no traditional Christian comfort or promise

of eventual justice or happiness for the good people. But the

message is ultimately one of hope. You can be a hero.

Shakespeare's "Hamlet" is full of talk about death,

dead bodies, murder, suicide, disease, graves, and

so forth. And there is no traditional Christian comfort or promise

of eventual justice or happiness for the good people. But the

message is ultimately one of hope. You can be a hero.

Hamlet, our hero, is the son of the previous king of Denmark,

also named Hamlet ("Old Hamlet", "Hamlet Senior" as we'd say),

who has died less than two months ago.

Hamlet remembers his father as an all-around good guy, and

as a tender husband who would even make a special effort to

shield his wife's face from the cold Danish wind.

The day Hamlet was born, Old Hamlet settled a land dispute

by killing the King of Norway in personal combat.

Hamlet, our hero, is the son of the previous king of Denmark,

also named Hamlet ("Old Hamlet", "Hamlet Senior" as we'd say),

who has died less than two months ago.

Hamlet remembers his father as an all-around good guy, and

as a tender husband who would even make a special effort to

shield his wife's face from the cold Danish wind.

The day Hamlet was born, Old Hamlet settled a land dispute

by killing the King of Norway in personal combat. Hamlet was

a college student at Wittenberg when his father died.

(Of course the historical Hamlet, who lived around 700,

could not have attended Wittenberg, founded in 1502).

The monarchy went to his father's brother, Claudius.

(Shakespeare and the other characters just call him "King".)

Hamlet's mother, Gertrude, married Claudius within less

than a month.

Hamlet was

a college student at Wittenberg when his father died.

(Of course the historical Hamlet, who lived around 700,

could not have attended Wittenberg, founded in 1502).

The monarchy went to his father's brother, Claudius.

(Shakespeare and the other characters just call him "King".)

Hamlet's mother, Gertrude, married Claudius within less

than a month. Exactly why Claudius

rather than Hamlet succeeded Old Hamlet

is not explained. Hamlet refers (V.ii) to

"the

election", i.e., the choosing of a new king by a

vote of a small number of warlords (as in Macbeth).

(By Shakespeare time, it was the Danish royal family

that voted.)

Interestingly, the Norwegian king is also succeeded by

his brother, rather than by his own infant son Fortinbras.

Exactly why Claudius

rather than Hamlet succeeded Old Hamlet

is not explained. Hamlet refers (V.ii) to

"the

election", i.e., the choosing of a new king by a

vote of a small number of warlords (as in Macbeth).

(By Shakespeare time, it was the Danish royal family

that voted.)

Interestingly, the Norwegian king is also succeeded by

his brother, rather than by his own infant son Fortinbras.

I.i.

I.i.

I.ii.

I.ii. Hamlet is left alone. He

talks to himself / the audience. Today's movie directors

would use voice-overs for such speeches ("soliloquies" if they

are long and the speaker is alone,

"asides" if they are short and there are other

folks on stage.) He talks about losing interest in life

and how upset he is by his mother's remarriage and its implications.

(In Shakespeare's era, it was considered morally wrong

to marry your brother's widow. Henry VIII's first

wife had been married to Henry's older brother, who died,

but the marriage had not been consummated. This puzzle sparked the

English reformation.)

Hamlet is trapped in a situation where things are obviously

very wrong. Like other people at such times, Hamlet wishes God hadn't forbidden suicide. Interestingly,

he does not mention being angry about not being chosen king.

Horatio, Marcellus, and Bernardo come in. Hamlet is surprised

to see his school buddy. Horatio says he's truant (not true),

and that he came to see the old king's funeral (not true --

he's much too late). Hamlet jokes that his mother's wedding

followed so quickly that they served the leftovers from the

funeral dinner. (I think Horatio

probably came to Elsinore out of

concern for Hamlet, spoke with the guards first, and was

invited at once to see the ghost. Some guys don't say to another guy,

"I came to see YOU" even when it's obvious.)

You'll need to decide what Hamlet means when he says that

he sees his father "in his mind's eye".

Sometimes, bereaved people notice their eyes fooling them --

shadows forming themselves in the mind into an image of the deceased.

Other mourners report even more vivid experiences that they do

recognize to be tricks of perception. Or perhaps Hamlet is simply

thinking a lot about his father, or holding onto his good memories.

The friends tell Hamlet about the ghost.

Hamlet asks what the ghost looked like -- skin color and beard

colors -- and agrees they match his father. Hamlet asks the

men to keep this a secret and to let him join them

the next night, hoping the ghost will return and talk.

Afterwards he says he suspects foul play. Everybody

else probably does, too, even without any ghost.

Hamlet is left alone. He

talks to himself / the audience. Today's movie directors

would use voice-overs for such speeches ("soliloquies" if they

are long and the speaker is alone,

"asides" if they are short and there are other

folks on stage.) He talks about losing interest in life

and how upset he is by his mother's remarriage and its implications.

(In Shakespeare's era, it was considered morally wrong

to marry your brother's widow. Henry VIII's first

wife had been married to Henry's older brother, who died,

but the marriage had not been consummated. This puzzle sparked the

English reformation.)

Hamlet is trapped in a situation where things are obviously

very wrong. Like other people at such times, Hamlet wishes God hadn't forbidden suicide. Interestingly,

he does not mention being angry about not being chosen king.

Horatio, Marcellus, and Bernardo come in. Hamlet is surprised

to see his school buddy. Horatio says he's truant (not true),

and that he came to see the old king's funeral (not true --

he's much too late). Hamlet jokes that his mother's wedding

followed so quickly that they served the leftovers from the

funeral dinner. (I think Horatio

probably came to Elsinore out of

concern for Hamlet, spoke with the guards first, and was

invited at once to see the ghost. Some guys don't say to another guy,

"I came to see YOU" even when it's obvious.)

You'll need to decide what Hamlet means when he says that

he sees his father "in his mind's eye".

Sometimes, bereaved people notice their eyes fooling them --

shadows forming themselves in the mind into an image of the deceased.

Other mourners report even more vivid experiences that they do

recognize to be tricks of perception. Or perhaps Hamlet is simply

thinking a lot about his father, or holding onto his good memories.

The friends tell Hamlet about the ghost.

Hamlet asks what the ghost looked like -- skin color and beard

colors -- and agrees they match his father. Hamlet asks the

men to keep this a secret and to let him join them

the next night, hoping the ghost will return and talk.

Afterwards he says he suspects foul play. Everybody

else probably does, too, even without any ghost.

I.iv.

I.iv. The ghost beckons Hamlet. Horatio warns him not to

follow, because the ghost

might drive him insane. Horatio notes that everybody

looking down from an unprotected large height thinks about

jumping to death (a curious fact). Hamlet is determined to

follow the ghost, and probably draws his sword on his

companions. (So much for the idea that Hamlet is psychologically

unable to take decisive action.) Hamlet says, "My fate cries

out", i.e., that he's going to his destiny. He walks off the stage

after the ghost. Directors often have Hamlet hold

the handle of his sword in front of his face to make a cross,

holy symbol for protection.

Marcellus (who like everybody else surely

suspects Claudius of foul play) says, "Something is rotten

in the state of Denmark" (usually misquoted and misattributed to

Hamlet himself.) Horatio says God will take care of Hamlet

("Heaven will direct it"). "Nay", says Marcellus, unwilling to

leave the supernatural up to God, "let's

follow him."

The ghost beckons Hamlet. Horatio warns him not to

follow, because the ghost

might drive him insane. Horatio notes that everybody

looking down from an unprotected large height thinks about

jumping to death (a curious fact). Hamlet is determined to

follow the ghost, and probably draws his sword on his

companions. (So much for the idea that Hamlet is psychologically

unable to take decisive action.) Hamlet says, "My fate cries

out", i.e., that he's going to his destiny. He walks off the stage

after the ghost. Directors often have Hamlet hold

the handle of his sword in front of his face to make a cross,

holy symbol for protection.

Marcellus (who like everybody else surely

suspects Claudius of foul play) says, "Something is rotten

in the state of Denmark" (usually misquoted and misattributed to

Hamlet himself.) Horatio says God will take care of Hamlet

("Heaven will direct it"). "Nay", says Marcellus, unwilling to

leave the supernatural up to God, "let's

follow him." I.v.

I.v. Hamlet says he'll remember what he's heard "while memory holds a

seat [i.e., still functions] in this distracted globe." By

"distracted globe", Hamlet probably means both "my distraught

head" and "this crazy world." (The name of the theater,

too.) Hamlet already has made up his

mind about Claudius and his mother, without the ghost's help.

So before considering whether the ghost is telling the truth,

Hamlet calls his mother a "most pernicious woman", and

says of Claudius "one may smile, and smile, and be a villain."

We all know that from experience -- most really

bad people pretend to be nice and friendly.

Hamlet says he'll remember what he's heard "while memory holds a

seat [i.e., still functions] in this distracted globe." By

"distracted globe", Hamlet probably means both "my distraught

head" and "this crazy world." (The name of the theater,

too.) Hamlet already has made up his

mind about Claudius and his mother, without the ghost's help.

So before considering whether the ghost is telling the truth,

Hamlet calls his mother a "most pernicious woman", and

says of Claudius "one may smile, and smile, and be a villain."

We all know that from experience -- most really

bad people pretend to be nice and friendly. II.ii.

II.ii. As before, Polonius can be a foolish busybody or a sinister

old man. (Foolish busybodies do not usually become

chief advisors to warrior-kings.)

Polonius launches into a verbose speech about finding the

cause of madness, prompting the queen to tell him to get

to the point ("More matter with less art"; the queen actually

cares about Hamlet.) He reads a love letter from Hamlet.

It's about the genuineness of his love. Polonius asks

the king, "What do you think of me?" The king replies, "[You are]

a man faithful and honorable." Now Polonius tells a lie. He emphasizes

that he had

no knowledge of Hamlet's romantic interest in Ophelia until she told him

and gave him the love letter. Polonius then truthfully tells how he

forbade Ophelia to see or accept messages from Hamlet.

However, Polonius does not mention the

wrist-grabbing episode. He then reminds the king of how reliable

an advisor he has always been, and says "Take this from this" (my head

off my shoulders, or my insignia of office from me; the actor will

show which is meant) "if this be otherwise." He finishes,

"If circumstances lead me [i.e., allow, the actor could say "let"], I will find /

Where truth is hid, though it were hid indeed / Within the

center [of the earth]." He suggests he and the king hide and watch

Ophelia and Hamlet. Polonius likes to spy.

As before, Polonius can be a foolish busybody or a sinister

old man. (Foolish busybodies do not usually become

chief advisors to warrior-kings.)

Polonius launches into a verbose speech about finding the

cause of madness, prompting the queen to tell him to get

to the point ("More matter with less art"; the queen actually

cares about Hamlet.) He reads a love letter from Hamlet.

It's about the genuineness of his love. Polonius asks

the king, "What do you think of me?" The king replies, "[You are]

a man faithful and honorable." Now Polonius tells a lie. He emphasizes

that he had

no knowledge of Hamlet's romantic interest in Ophelia until she told him

and gave him the love letter. Polonius then truthfully tells how he

forbade Ophelia to see or accept messages from Hamlet.

However, Polonius does not mention the

wrist-grabbing episode. He then reminds the king of how reliable

an advisor he has always been, and says "Take this from this" (my head

off my shoulders, or my insignia of office from me; the actor will

show which is meant) "if this be otherwise." He finishes,

"If circumstances lead me [i.e., allow, the actor could say "let"], I will find /

Where truth is hid, though it were hid indeed / Within the

center [of the earth]." He suggests he and the king hide and watch

Ophelia and Hamlet. Polonius likes to spy. Hamlet

levels with his friends. There was a time when the

beauty of the earth, the sky, and the thoughts and accomplishments of

the human race filled him with happiness. (All of this is

good Renaissance thought, and familiar from many times and places -- and

I hope you've felt this as well.)

Now he has lost

his ability to derive enjoyment,

though he knows the earth, sky, and people should still

seem wonderful.

They seem instead to be "the quintessence of dust".

Anyone who's experienced depression knows the feeling.

"Quintessence" ("fifth essence"; compare Bruce Willis's

"Fifth Element") was an idea from prescientific

thought -- a mystical substance that made fire, air, water, and earth

work together, and supposedly what the planets and stars were made of.

Hamlet

levels with his friends. There was a time when the

beauty of the earth, the sky, and the thoughts and accomplishments of

the human race filled him with happiness. (All of this is

good Renaissance thought, and familiar from many times and places -- and

I hope you've felt this as well.)

Now he has lost

his ability to derive enjoyment,

though he knows the earth, sky, and people should still

seem wonderful.

They seem instead to be "the quintessence of dust".

Anyone who's experienced depression knows the feeling.

"Quintessence" ("fifth essence"; compare Bruce Willis's

"Fifth Element") was an idea from prescientific

thought -- a mystical substance that made fire, air, water, and earth

work together, and supposedly what the planets and stars were made of.

The

players arrive, heralded by Polonius, who Hamlet

calls a big baby. Hamlet fakes madness for Polonius's benefit.

He pretends he was talking about something else with his friends,

refers obliquely to Ophelia, and gives a Bronx cheer ("Buzz buzz").

When the players arrive, Hamlet drops the pretense of madness,

and greets old friends. One actor repeats a bombastic speech

on the fall of Troy, overacting with tears in his eyes.

The

players arrive, heralded by Polonius, who Hamlet

calls a big baby. Hamlet fakes madness for Polonius's benefit.

He pretends he was talking about something else with his friends,

refers obliquely to Ophelia, and gives a Bronx cheer ("Buzz buzz").

When the players arrive, Hamlet drops the pretense of madness,

and greets old friends. One actor repeats a bombastic speech

on the fall of Troy, overacting with tears in his eyes. Hamlet soliloquizes. He calls himself a "rogue" and a

"peasant slave". A rogue was a dishonest person; a

peasant slave was an oppressed farm worker. He talks about

how the actor got himself all worked-up over something about

which he really cared nothing (the fall of Troy). Hamlet

contrasts this with his own passiveness in both word and deed.

What does Hamlet

really mean? He reminds us, at the end of the soliloquy, that even

though he thinks the ghost is telling the truth, he needs to be sure

this is not a demonic deception.

In the meantime, though, he hates Claudius with a silent hatred

that contrasts with the actor's fake show. Hamlet calls himself

"gutless" ("I am lily-livered and lack gall").

Hamlet soliloquizes. He calls himself a "rogue" and a

"peasant slave". A rogue was a dishonest person; a

peasant slave was an oppressed farm worker. He talks about

how the actor got himself all worked-up over something about

which he really cared nothing (the fall of Troy). Hamlet

contrasts this with his own passiveness in both word and deed.

What does Hamlet

really mean? He reminds us, at the end of the soliloquy, that even

though he thinks the ghost is telling the truth, he needs to be sure

this is not a demonic deception.

In the meantime, though, he hates Claudius with a silent hatred

that contrasts with the actor's fake show. Hamlet calls himself

"gutless" ("I am lily-livered and lack gall").  Hamlet's

famous speech on whether it's worthwhile

living or doing anything needs little comment.

He says it seems to him that life is not worth living,

mostly because people treat each other so stupidly

and badly. We also suffer from disease and old age --

even living too long is a "calamity".

But Hamlet foregoes suicide because

"something after death" might be as bad or worse,

if we've taken our own lives or haven't lived.

He's saying what many people have felt, especially

those who do not assume that the Christian account

of the afterlife is true -- or even that there is any afterlife.

Notice that Hamlet says that nobody's returned to

tell of the afterlife -- the ghost notwithstanding.

Shakespeare seems to be saying, loud and clear, "Don't

focus on the story. Focus on the ideas."

Some people have been puzzled by the lines "Thus conscience

does make cowards of us all; / And thus the native hue of

resolution / Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, /

And enterprises of great pitch and moment / With this

regard their currents turn awry / And lose the name of action."

Not only is Hamlet talking about actual suicide -- he's also

talking about "lifelong suicide" by doing nothing,

choosing the easy passive approach to life.

Compare this to Hamlet's calling himself gutless merely

because he can't kill the king until he has all the facts

and a good opportunity. It's human nature to feel

cowardly and ineffective when you're unable (or too smart) to take

decisive (or rash) action.

Hamlet's

famous speech on whether it's worthwhile

living or doing anything needs little comment.

He says it seems to him that life is not worth living,

mostly because people treat each other so stupidly

and badly. We also suffer from disease and old age --

even living too long is a "calamity".

But Hamlet foregoes suicide because

"something after death" might be as bad or worse,

if we've taken our own lives or haven't lived.

He's saying what many people have felt, especially

those who do not assume that the Christian account

of the afterlife is true -- or even that there is any afterlife.

Notice that Hamlet says that nobody's returned to

tell of the afterlife -- the ghost notwithstanding.

Shakespeare seems to be saying, loud and clear, "Don't

focus on the story. Focus on the ideas."

Some people have been puzzled by the lines "Thus conscience

does make cowards of us all; / And thus the native hue of

resolution / Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, /

And enterprises of great pitch and moment / With this

regard their currents turn awry / And lose the name of action."

Not only is Hamlet talking about actual suicide -- he's also

talking about "lifelong suicide" by doing nothing,

choosing the easy passive approach to life.

Compare this to Hamlet's calling himself gutless merely

because he can't kill the king until he has all the facts

and a good opportunity. It's human nature to feel

cowardly and ineffective when you're unable (or too smart) to take

decisive (or rash) action. Hamlet sees Ophelia, reading a book. He assumes it's her

prayer book (she is evidently not much of a pleasure reader), and asks

her to pray for the forgiveness of his sins. Instead, she

tries to give him back his love letters, saying he has

"prove[d] unkind", which is ridiculous. Hamlet immediately

realizes that she has been put up to this. He responds like

a thoughtful man of strong feelings.

He generalizes his disappointment with the two women in his life

to all women -- I think unfairly. (Watch how his attitude toward women matures later in the play.)

But the Olivier movie's torrent of loud verbal abuse seems wrong.

Showing Hamlet's emotional turmoil and conflict seems better.

Rather, Hamlet sees Ophelia being corrupted by the world

with which he feels he has already had to compromise.

He doesn't want this to happen to the girl about whom

he cares so much. Like most men

during breaking up, he says "I loved you" and "I didn't love you".

More meaningfully, Hamlet talks about fakeness. He asks

where her father is, and must know that she is lying.

(In Ethan Hawke's version, he finds a wire microphone hidden

on Ophelia.)

He wants Ophelia to remain good,

even as he sees himself becoming compromised. She would have

an opportunity to renounce the world by joining a convent, and

he urges her to do so.

(Decide for yourself about anything anybody may tell you about

"nunnery" being Hamlet's double-meaning for "whorehouse".

I can't make sense out of this in the present context.)

In our world, even being beautiful drives people to be dishonest.

Disgusted with the world,

Hamlet suggests that there

be no more marriages -- suicide for the human race.

Hamlet sees Ophelia, reading a book. He assumes it's her

prayer book (she is evidently not much of a pleasure reader), and asks

her to pray for the forgiveness of his sins. Instead, she

tries to give him back his love letters, saying he has

"prove[d] unkind", which is ridiculous. Hamlet immediately

realizes that she has been put up to this. He responds like

a thoughtful man of strong feelings.

He generalizes his disappointment with the two women in his life

to all women -- I think unfairly. (Watch how his attitude toward women matures later in the play.)

But the Olivier movie's torrent of loud verbal abuse seems wrong.

Showing Hamlet's emotional turmoil and conflict seems better.

Rather, Hamlet sees Ophelia being corrupted by the world

with which he feels he has already had to compromise.

He doesn't want this to happen to the girl about whom

he cares so much. Like most men

during breaking up, he says "I loved you" and "I didn't love you".

More meaningfully, Hamlet talks about fakeness. He asks

where her father is, and must know that she is lying.

(In Ethan Hawke's version, he finds a wire microphone hidden

on Ophelia.)

He wants Ophelia to remain good,

even as he sees himself becoming compromised. She would have

an opportunity to renounce the world by joining a convent, and

he urges her to do so.

(Decide for yourself about anything anybody may tell you about

"nunnery" being Hamlet's double-meaning for "whorehouse".

I can't make sense out of this in the present context.)

In our world, even being beautiful drives people to be dishonest.

Disgusted with the world,

Hamlet suggests that there

be no more marriages -- suicide for the human race. Ophelia thinks Hamlet, who she admired so much, is crazy.

(Once again, being genuine looks like insanity.)

But the king comes out and says that he thinks that Hamlet

is neither in love, nor insane, but very upset about something.

Polonius decides he'll get Hamlet to talk to his mother next,

while Polonius eavesdrops again. Polonius likes to spy.

The king decides that he will send Hamlet to England

"for the demand of our neglected tribute" (i.e., to ask

for protection money.)

Ophelia thinks Hamlet, who she admired so much, is crazy.

(Once again, being genuine looks like insanity.)

But the king comes out and says that he thinks that Hamlet

is neither in love, nor insane, but very upset about something.

Polonius decides he'll get Hamlet to talk to his mother next,

while Polonius eavesdrops again. Polonius likes to spy.

The king decides that he will send Hamlet to England

"for the demand of our neglected tribute" (i.e., to ask

for protection money.) Hamlet tells Horatio to watch the king as the players

re-enact the murder of Old Hamlet. Hamlet jokes -- first

bawdily, then about how his mother looks cheerful

despite his father having died only two

hours ago. (Ophelia, who is literal-minded and

thinks he is crazy, corrects him.)

Hamlet tells Horatio to watch the king as the players

re-enact the murder of Old Hamlet. Hamlet jokes -- first

bawdily, then about how his mother looks cheerful

despite his father having died only two

hours ago. (Ophelia, who is literal-minded and

thinks he is crazy, corrects him.)

The

play begins with a "dumb show", in which the story is

pantomimed. The king and the queen profess

love, the king falls asleep, and the villain pours poison in the

king's ear and seduces the queen. If Polonius is a sinister old

man and Claudius's accomplice,